On display at the Kalamazoo Air museum

Friday, June 30, 2017

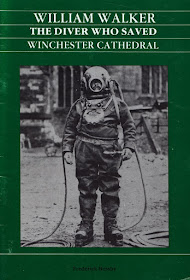

William Walker: The Diver Who Saved Winchester Cathedral

I found this fascinating booklet at a Brockville thrift shop some time ago. First published in 1970, this was the 1987 Third Edition produced by The Friends of Winchester Cathedral.

In 1905, an architect reported that the west end of the cathedral, in the crypt, was leaning outward dangerously. This was a thirteenth-century addition to the original Anglo-Norman structure, and the later builders had created a timber raft under the foundations to spread the load. A good idea in theory, but unfortunately it floated on a thick peat bed. This had slowly compressed over the centuries, allowing the building to shift away from the main structure. Under the peat, however, was a bed of hard gravel, which would provide a solid foundation. The problem was that the gravel bed was fifteen feet below the level of the water table. Francis Fox, a consultant engineer made a number of recommendations, including the grouting of the walls to be achieved by pumping liquid cement into the loose rubble core. About 500 tons of this grout was used.

Fox also recommended underpinning the walls down to the hard gravel. To do this, the original beech logs were sawn out by hand. Surprisingly, they were perfectly preserved. Digging down through the peat proved much more difficult, since the water rushed in and filled the excavation area to a depth of 13 feet. Powerful pumps could not keep up with the flow, to which was added the concern that the pumps might actually start sucking out solid material from beneath the walls, leading to their collapse. In 1906, Fox got the idea to use a diver to do the work. William Walker was chosen for the job. Born in London in 1869, entering the Royal Navy and becoming a fully qualified diver. In 1892 he left the navy to join the famous firm of Siebe Gorman & Company, becoming their chief diver out of an international staff of more than 200 divers.

Between 1906 and 1911, Walker worked in 13 feet of black, soupy peat water, made even more vile by the fact that it also irrigated the crypt. Over five years, he handled 25,800 bags of concrete and 114,900 concrete blocks, building them up from the gravel bed to the bottom of the cathedral's stone foundations. In those days, the diver's suit weighed 200 pounds, including 18 pounds for each boot. He also wore 40 pound lead weights on his chest and back. On top of that was his 30 pound helmet. Although buoyancy in the water helped compensate for some of this weight, it was still extremely burdensome, especially realizing that Walker was 37 years old at the time the work began.

When the work was completed in August 1911, the cathedral presented Walker with an inscribed silver rose bowl. Walker was very honoured by the gift, but more was to come. In 1912, Walker was summoned to Buckingham Palace to receive the Royal Victorian Order, an honour under the exclusive control of the King. Walker wrote to his employers:

"I have received a letter commanding me to be at Buckingham Palace on the 19th to receive the Royal Victorian Order at the request of His Majesty. I would be grateful if you would inform me how to go on and anything I could do for the firm, and I must thank you with all my heart for all you have done for me in the past."

Naturally, the firm was all too pleased to permit him time off to attend the ceremony and in due course he was presented with the order by King George V, who shook his hand and thanked him for his work in saving the cathedral.

Tragically, William Walker succumbed to influenza in the terrible epidemic of 1918. In 1964, a statuette in Walker's honour was commissioned. Sir Charles Wheeler was given the task and, when the statuette was unveiled, it was revealed to be that of Francis Fox in a diving suit. The two men couldn't have been more different in appearance: Walker was burley, 14-stone and moustached, while Fox was slight and clean shaven. It was believed that the Sir Wheeler may have based the sculpture on the wrong figure from a group photograph! Duh!

It wasn't until 2001 that this error was corrected and a new statue bearing Walker's likeness was installed at the cathedral. An article in The Telegraph had this to say:

The Dean of Winchester, the Very Rev Michael Till, said: "There has been embarrassed recognition that the attempt to honour Walker turned into a bit of a disaster, but the story is too good to leave like that and now it has come right.

Very Rev Till said: "We don't tend to draw attention to the error in the statue, but there is a lot of attention drawn to Walker. Without him we would be looking at a rather shorter cathedral. We would still have the longest nave in Europe but the sanctuary would be the shortest." The new 15-inch bronze statue, which is costing £9,000, has been created by Glynn Williams, the Professor of Sculpture at the Royal College of Art.

Reg Vallintine, the vice-chairman of the Historical Diving Society, which was behind the initiative to erect the new statue, said: "It was awful for the families when the first statue was unveiled. There, instead of the features of Walker, was the pointed face of the surveyor. It wasn't the cathedral's fault, though, and we are delighted that it is doing this. It is time to right this wrong."Damn straight.

Vanished Tool Brands: Twist-Lock Power Tools

I recently found these two tools together in a box at a thrift store. The circular saw attachment was clearly never used (the small circular saw is still in its original plastic bag) but the oscillating sander had been put to work by a previous owner at some point.

These kind of electric drill accessories were popular in the 1960's before special purpose tools eclipsed them. They were offered by huge tool companies like Millers Falls, and also by small and mysterious firms like ETC and Arrow Metal Products.

The Twist Lock name referred to the means of attaching the accessories to an electric drill. The tool came with an adaptor, which apparently only fit one model of drill. The adaptor then twisted onto the receiver on the tool accessory, locked in place with a spring loaded pin (with conical handle, shown on left in the photo below). Altogether, it's a nicely made piece of equipment.

The tools were made by Portable Electric Tools, Inc. out of Chicago, and marketed under their broader "Shopmate" brand. The Twist-Lock feature doesn't appear to have lasted long. The only two ads I can find for the brand are from 1960:

|

| Popular Mechanics, April 1960 |

|

| Popular Mechanics, March 1960 |

Thursday, June 29, 2017

Indianapolis 500 winner,1925

A Little Italian Girl, 1901

|

| Happy Hours in Story Land. New York: McLoughlin Brothers, 1901. |

According to Destination America, "Between around 1880 and 1924, more than four million Italians immigrated to the United States, half of them between 1900 and 1910 alone—the majority fleeing grinding rural poverty in Southern Italy and Sicily." The page above shows one of the results.

Vanished Tool Makers: Anglo Scottish Tool Company, Gateshead, England

Above, a "Rapier" No. 1 Archimedes screwdriver made by this company.

The Anglo Scottish Tool Company was located in Gateshead, U.K., across the Tyne River from Newcastle-on-Tyne. They were best know for their line of "Rapier" metal planes and spokeshaves. From what I can find online, their planes were of indifferent quality. The driving force behind the company seems to have been one William Sidney Powel, to whom a number of British manufacturing patents were issued starting in the 1930's and assigned initially to the Powel & Hill Company, which became the Anglo Scottish Tool Company. In about 1946 the company apparently became Adams Powel Equipment Ltd. Under that name the company persisted into the early 1970's, when they were honoured with a Queen's Award to Industry for their export achievement.

The company's name is peculiar, since its location was a good 60 miles from the Scottish border. I don't think the name would play well today against the strong sense of Scottish independence.

|

| Source: Gateshead History |

During its heyday, the company's tools were distributed in England and Scotland through H. & D. Churchill Ltd. of London.

Simpson's lending library

In a used book store I opened the cover of an old book, to find that it had once belonged to one of Canada's major department stores. The use of the apostrophe indicates this was pre-1972. This was a different era of retail, when companies took care of their people, imagine Walmart actually maintaining an in-house library!

Simpson's was in business from 1858 till the early 1980s when it was acquired by its competitor, the Hudson Bay company. It was half owner of the popular Simpsons Sears (later Sears Canada) chain begun as a partnership with Sears Roebuck in the early 1950s. The last vestige of this empire is barely hanging on, Sears Canada having recently filed for bankruptcy.

Wednesday, June 28, 2017

Another job you wouldn't want to do. Taping ribs.

Steam train demonstration

Jeweller's saws

This is a lovely clamp-style saw with an adjustable

frame. Sadly, for such a well-made

tool, the manufacturer did not see fit to leave its name on it.

Below, another made by Dixon, apparently a German firm:

|

| Louis A. Shore. Arts and Crafts for Canadian Schools. J.M. Dent & Sons (Canada) Ltd., 1946. |

The jeweller's saw is in the class of coping saws. The history of the coping saw seems to be something of

a mystery. In the 19th century,

there were marquetry saws with deep throats and frame saws with shallow throats

used for cutting dense materials. The coping saw appears to be a tool that

bridges these two forms. The first U.S. patent for a saw that looks like a

modern coping saw is an 1883 application from William Jones for a “saw frame

for a jeweler’s saw.” The following

year, C.A. Fenner patented a mechanism that allowed the blade to rotate in the

frame (it's amazing in its gizmosity). He called it (most unhelpfully) a

"hand saw." In 1887, Christopher Morrow patented a tool called a

"coping saw," which ironically tensions its blade more like a wooden

bowsaw. After that point, the term "coping saw"

crops up regularly in catalogues and patent filings. By 1900, the saw is

everywhere.

Tuesday, June 27, 2017

Case Traction Engines, 1908

|

| Floyd Clymer, Album of Historical Steam Traction Engines, Bonanza Books |

Osmiroid Basic Calligraphy

Above, the a few pages from a booklet I turned up. There's lots of information on the firm of E.S. Perry on the web, so I won't repeat it here. Suffice it to say, that British company has vanished along with so many others. Personally, I think their branding left something to be desired. Osmiroid? Sounds like an ointment for piles.

If anyone's interested in looking at the full booklet, I've uploaded it here:

Monday, June 26, 2017

Making WAVES in WWII

Vanished Tool Makers: James Hartley & Co., Sunderland, England

I found this beautiful old glass cutter at a ReStore recently. The handle is a lovely, open-grained wood and the ferrule is brass. The head is steel, and has a set screw for holding a carrier for an industrial diamond. The diamond is very worn so this tool saw heavy use.

The firm of James Hartley wasn't really a tool firm--they made glass. In 1836, the Hartley brothers set up their own glass-making business in Sunderland, on the north-east coast of England, formerly better known as Wearmouth. There they established the Wear Glass Works and traded as James Hartley & Co. In 1838, building on German technology, James was granted a patent for Hartley's Patent Rolled Plate. For the next 50 years, this would be the company's major product.. In fact, by the 1860's, the firm was using this process to make one-third of all the glass made in England and employing up to 700 workers. Jame's heirs lost but then regained control of the business in the 1890's, but the company was finally rolled up in 1915. So, my glass cutter is at least a century old.

The story didn't end there, though. One son continued making coloured glass as Hartley, Wood & Co., which was eventually taken over by Pilkington's in 1982. (The British Pilkington company invented the Float Glass Process in the 1950's, a revolutionary method for producing flat glass by floating molten glass over a bath of liquid tin.) The original company continued under the Hartley, Wood name until 1997. The National Glass Centre was built in 1998 in the interests of preserving the skills of these glass-makers, but went into bankruptcy only two years later. In 2005, Pilkington was acquired by a Japanese company, NSG.